‘Everything Is Terrible, but I’m Fine’

A mentality that explains a lot about the economy, electoral politics, and human nature

Sign up for Derek’s newsletter here.

In May, the Federal Reserve published a report on the economic well-being of American households in 2021. This survey is infamous for revealing, in 2013, that half of Americans couldn’t cover a $400 emergency with spare cash. An Atlantic magazine cover story called it “The Secret Shame of the Middle Class.”

In 2021, the findings were surprisingly positive, especially given the relentless heartrending punishment that is the 2020s news cycle. Self-reported financial well-being increased to the highest percentage in the nine-year history of the survey. As for that $400 emergency payment, more than two-thirds of adults now say that they can make it. This key measure of financial security improved 40 percent, during a pandemic.

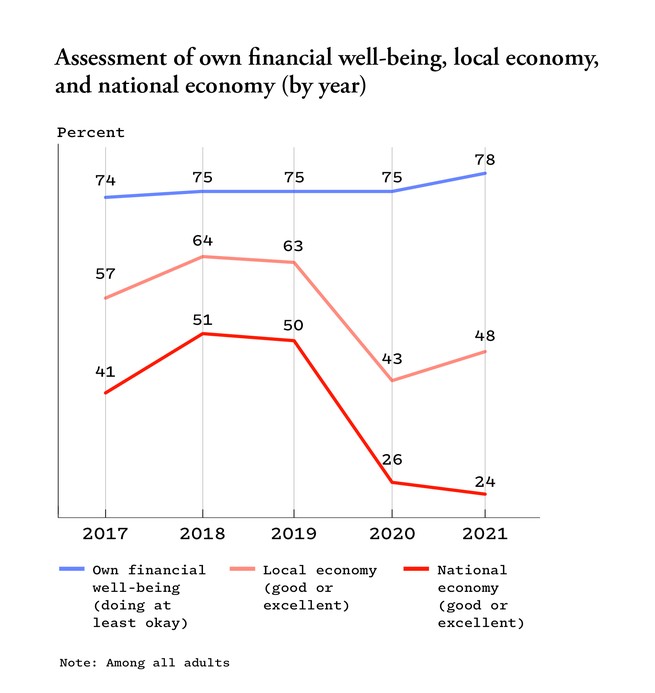

Now here’s where things get weird. The Fed also asked Americans how they felt about the local and national economy. And though the number of Americans who said that they personally were “doing at least okay” actually rose slightly from 2019 to 2021, their evaluation of the national economy plummeted in that time frame. If this graph were a bumper sticker, it would read: Everything is terrible, but I’m fine.

So what’s going on here? Why is the gap between “how I’m doing” and “how America is doing” so dramatic?

One answer is that the Everything is terrible but I’m fine philosophy is something close to human nature. At least, people all over the world tend to be individually optimistic and socially pessimistic.

Here’s a concrete example. Ipsos, a global market-research company, has a survey called Perils of Perception, which asks people in dozens of countries to report their own happiness and guess the average happiness of their fellow citizens. In every country they survey, people self-report much higher happiness than they guess other people feel. At the extreme are South Koreans, who estimate that 25 percent of South Koreans are happy, whereas nearly 90 percent say that they are themselves “very happy” or “rather happy.” The perception gap in the U.S. is smaller and closer to the international average: Americans estimate that 50 percent of other Americans are happy, but about 90 percent of them say that they’re actually happy.

But there’s one obvious problem with this explanation: It doesn’t capture change over time. Look at that Federal Reserve graph again. The divergence between “own financial well-being” and “national economy” started rather large—and then, in 2020, it became absolutely humongous.

Yes, there was a pandemic. Yes, people were locked in their houses, reading news about a deadly virus. Yes, they were alerted to the closure of thousands of businesses and the flash-freezing of the U.S. economy, even as the federal government bailed out firms and households with loans, eviction moratoriums, suspended student-debt payments, and several rounds of checks. But then the economy improved in 2021, and Americans got even more pessimistic. This shift can’t be explained by the fact that evaluations of the national economy are highly partisan, and that Republicans, for example, lost confidence in the economy when their guy left office. No amount of Democratic optimism made up the difference.

Something deeper is happening. Even outside economics and finances, a record-high gap has opened up between Americans’ personal attitudes and their evaluations of the country. In early 2022, Gallup found that Americans’ satisfaction with “the way things are going in personal life” neared a 40-year high, even as their satisfaction with “the way things are going in the U.S.” neared a 40-year low. On top of the old and global tendency to assume most people are doing worse than they say they are is a growing American tendency to be catastrophically gloomy about the direction of this country, even as we’re resiliently sunny about our own household’s future.

This has some interesting implications for White House officials wondering why their popularity imploded even as the American consumer got stronger. Checking accounts bloomed, but our spirits soured. It might also provide a subtle warning for politicians who want to push Americans to a radically new place on policy. Sure, voters like to hate things at the national and abstract levels, which seems to open the door for bold change. But because most Americans say they’re personally fine, they might resist too much experimentation. This creates a confusing voting bloc, which is constantly angry about the state of things, but also fundamentally conservative about any change that overturns their “rather happy” life and “at least okay” finances.

I have a final theory of what’s going on here. With greater access to news on social media and the internet, Americans are more deluged than they used to be by depressing stories. (And the news cycle really can be pretty depressing!) This is leading to a kind of perma-gloom about the state of the world, even as we maintain a certain resilience about the things that we have the most control over. Beyond the diverse array of daily challenges that Americans face, many of us seem to be suffering from something related to the German concept of weltschmerz, or world-sadness. It’s mediaschmerz—a sadness about the news cycle and news media, which is distinct from the experience of our everyday life. I’m not entirely sure if I think this is good or bad. It simply is. Individual hope and national despair are not contradictions. For now, they form the double helix of the American spirit.